I returned from Saarbrücken with a pocket full of train tickets, sticky notes that appear to have withstood a minor storm, and a head full of panels. As everyone yells “AI!” in the hallway, DeGEval‘s annual gathering leaned heavily into the big questions of our day: how evaluation becomes institutionalized, how it remains useful, and how it maintains its soul. In this piece, I write about the four lessons I’m taking with me to work and home.

AI is having a moment: good and bad, sometimes at the same time

First, Artificial intelligence has the potential to speed up coding, reveal patterns, and reduce the intimidating nature of large evidence sets. A cautionary chorus that reiterated often during the conference was “AI is being promoted while evaluation is being diminished”. It’s easy to overlook the discussions that give evidence meaning, that is, consent, power, context, and consequence, when flashy tools promise instant knowledge. Evaluation with AI, guided by humans who understand when speed is beneficial and when it is detrimental, is the solution, not evaluation or artificial intelligence. In actuality, this might mean treating GenAI as a junior analyst, recording its usage in each study, and implementing bias checks on a regular basis, much like data cleaning. Faster iteration without sacrificing the ethics and judgment that lend credibility to our work is the result.

Institutionalizing evaluation is political, not just technical

Second, law, funding, and advocates are necessary if you want evaluation to last beyond a project. That was the underlying theme of each international stream session. Although countries and organizations have written policies, their execution is uneven, underfunded, and quickly delayed when political agitation flares up. Jakob von Weizsäcker of the Ministry of Finance of Saarland, instructively mentioned how evaluators need to also have subject domain experts on government internal workings. He shared an example of how having a domain expert encouraged the government to carry out COVID19 rapid evaluations. Other conversations included how we discuss “capacity” as if it were training hours, but in practice, it is calendars, committees, and money. When audit offices follow through, ministries have mandates, parliaments demand proof, and a powerful person asks “where’s the evaluation?” before funding is transferred. At that point, institutionalization is successful. It is our responsibility to normalize that expectation. To make a policy more than a press release, this entails utilizing public dashboards, coordinating VOPE (Voluntary Organizations for Professional Evaluation) inputs with budget cycles, engaging government domain experts and presenting findings in formats that are ready for decision-making.

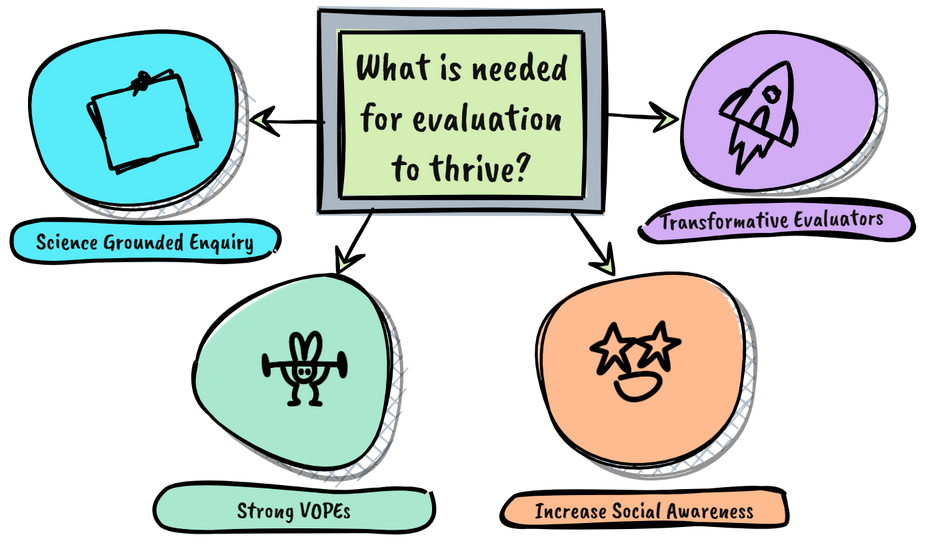

Capacity building without a consistent structure is just party planning

Third, it’s healthy that this one hurt a little. Northern credentials, brief workshops, one-time training, non-academic training without quality assurance and coordination are still the mainstays of the field, and they have no bearing on who gets to perform important tasks. Some of the conversation demanded genuine coordination, more robust quality assurance, and mentorship pathways. While everyone still relates with anything “traditional monitoring and evaluation”, interest in transformational approaches such as indigenous and cultural approaches is waning because people don’t see the path or the reward. One of the slide presentations by Dr Steffan, shows how there is decreasing demand at MSc level owing to awareness. At the same time, there are few institutions offering evaluation related courses. We are capable of more. Opportunities can be redistributed through apprenticeship models based on live evaluations, paid positions for aspiring evaluators, portfolio reviews and micro-credentials with explicit standards, and regional trainers who aren’t parachuted in. We can determine whether “capacity” is something we share or something we gatekeep by asking who designs, who learns, who advances, and who benefits.

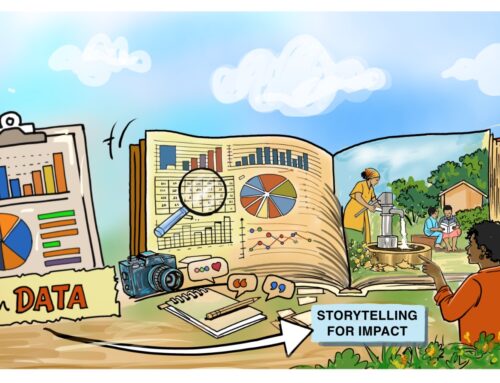

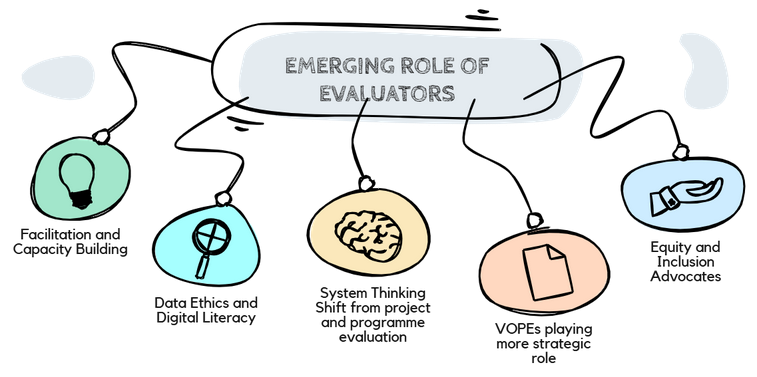

From Insiders to Influencers: the new public-facing roles of evaluation

Fourth, whispering to itself won’t help the field flourish. Too little of our work reaches the people whose lives the programs affect, and too much of our communication is written for insiders. Roles that make evaluation relatable, visible, and agenda-shaping are what we need. Systems thinkers are able to convert project results into policy narratives that illustrate how minor adjustments add up to significant change. Advocates for equity and inclusion can publish whose voices were heard, and whose were not, and then design with communities, not just for them. Pragmatists who understand AI can push back where it could cause harm, disclose where it can be beneficial, and use automation where it can be beneficial. VOPE strategists can move from networking to agenda-setting by timing their contributions to legislative and budget moments, bringing journalists and civil society into the conversation before reports are signed off.

Why this matters now

We were compelled by the conference theme to link evaluation to improved governance rather than merely better reports – Many thanks to CEval and other organisers. That won’t just happen. If we treat institutionalization as a political craft with mandates and funding, if we rebuild capacity building around shared knowledge and real practice, if we keep AI within evaluation without letting it hollow out the field, and if we boldly move from insider circles into public squares, it will happen. Or, to paraphrase my previous sticky note, we must rise, not just in terms of skills, but also in terms of purpose, in a world that desperately needs evaluations.