Participants frequently sign consent forms for Monitoring, Evaluation, Research, and Learning (MERL) processes without fully understanding the risks, benefits, or alternatives associated with their involvement. Let me share a personal moment from the field that brought the importance of informed consent into sharper focus for me.

During a study I was coordinating in a rural set-up in Bomet County, Kenya, looking at a cash transfer program. We met Jane (not her real name), a young woman who seemed interested at first. We gave her the official consent form, like we always do.

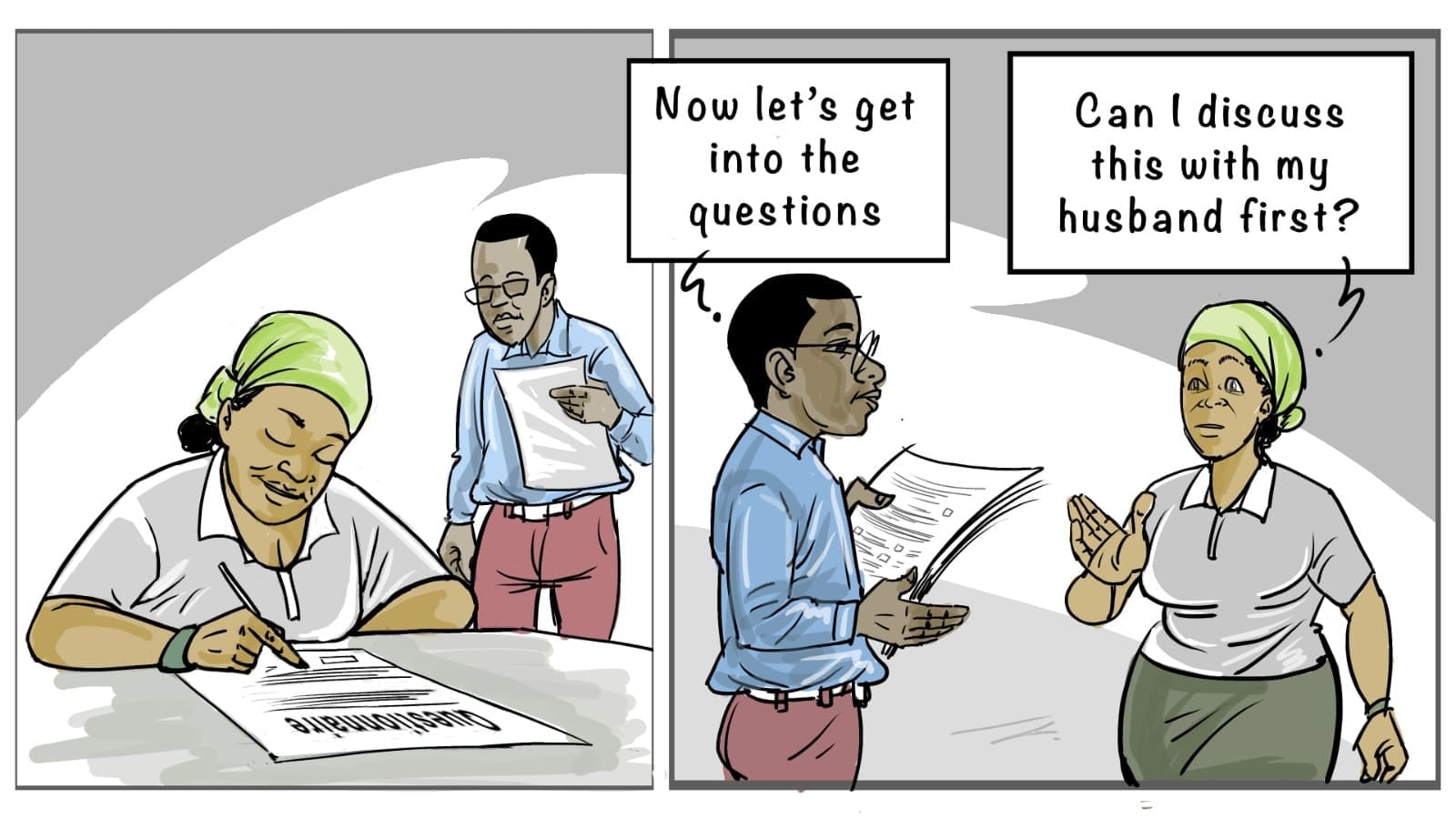

But later, when we went to interview her, she hesitated. Quietly, she asked if she could discuss it with her husband first. In her community, big decisions, especially for women, are often made together with family. That simple request hit me hard. It wasn’t just about getting her signature on paper. Consent wasn’t done just because we handed her a form.

We stopped right there. “Of course, take the time you need,” I said. We walked away to give her space. When Jane came back, she had questions. Real questions: “Who exactly sees my answers?” “Can this affect my family’s aid?” “What if I change my mind later?” This was our real chance for consent. We put the complicated form aside. We talked, in words she understood, answering every worry patiently. We made it clear: her choice mattered completely.

The change in Jane was amazing. The hesitation was gone. She wasn’t just signing something because she felt she had to. She understood, and she chose freely to share her story. You could see she felt respected, even a little empowered. She became an active partner in our work, not just someone we were collecting information from.

That day with Jane taught me a great deal. I learned that real consent is a conversation, not just a form. It starts with a paper, but it only truly happens when people understand and freely agree. That means listening, answering questions simply, and respecting their way of life, like needing time to talk with family.

I saw how informed consent upholds dignity and builds trust. Because Jane felt valued and safe, she shared openly and honestly. This meant our findings weren’t based on someone just going along with things; they were built on real trust, making our whole study stronger and more credible.

And yes, doing consent right has real hurdles. It takes time. Language can be tricky. There’s always pressure to move faster. It is easier to just get the signature and go. But Jane showed me clearly that cutting corners on consent breaks trust and compromises the quality of our work. Skipping that real conversation risks everything we’re trying to achieve.

So now, I see consent differently. It’s not a box to tick off at the start. It’s an ongoing, essential talk built on respect. It requires patience, listening, and adapting to people’s lives. When we get it right, like we finally did with Jane, something powerful happens. People move from being just “participants” we study to becoming real partners in understanding what’s happening. And that doesn’t just feel ethical, it makes our work genuinely better and more true to life. Would you want to share your experience with informed consent? Kindly use the comment box. I’d love to read your story, too.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Fidelis Nasong’o is a Programme Officer with over five years’ experience in education and international development across Kenya and a Cloneshouse African Internship Programme intern. He has led program implementation, stakeholder engagement, and field research with Instill Education and Innovations for Poverty Action. Fidelis holds a Bachelor’s in Education and is completing a Master’s in Project Planning and Management at the University of Nairobi. He’s passionate about using data to strengthen educational outcomes and program impact.

This reminds me of a similar experience in my work. While conducting household surveys, an elderly participant readily signed the consent form. It was only later that I realized he couldn’t actually read it. Situations like this are quite common but often overlooked. Language barriers also play a significant role; even when using local languages, some terms are difficult to translate accurately, which can create further misunderstandings.

Thank you for sharing this experience, it really highlights how nuanced informed consent can be in practice. As you noted, literacy levels and language barriers often complicate the process, even when researchers are careful. It’s a reminder that beyond translation, we also need culturally sensitive ways of checking understanding, like verbal explanations, visual aids, or interactive questioning. These small adjustments can go a long way in ensuring participants are truly informed, not just formally compliant.

What a concrete description of important values in data collection by being very clear on the first important concept of consent signing! This gives a whole description of the consent and its importance especially to the illiterate respondents.Thumbs up to the writer

Thank you for your feedback! You’re absolutely right, consent is more than just a signature; it’s about ensuring that every participant, including those who may not be literate, truly understands what they are agreeing to. Highlighting and practicing this value in data collection helps build trust and strengthens the credibility of our work.

Thank you for sharing this, Fidelis. It really resonated with me. While working on a participatory research project in Nairobi, I interviewed an elderly gentleman who signed the consent form. Still, later I realized he hadn’t fully understood what he had agreed to. That moment was a turning point for me: consent is not about collecting a signature, but about ensuring comprehension. I later came to appreciate how an accompanying information sheet can help bridge gaps, especially in communities where language, literacy, and cultural differences complicate understanding.

Your point that consent is an ongoing conversation is so true. When done correctly, it builds trust and turns participants into genuine partners rather than just subjects of research.

Thank you for sharing this thoughtful reflection. Your experience in Nairobi captures so well the heart of the matter, consent is far more than a signature, it’s about genuine understanding.

You’re absolutely right that tools like information sheets, when used thoughtfully, can make a real difference in bridging gaps. Treating consent as an ongoing conversation not only safeguards participants but also fosters the kind of trust that makes research truly participatory.

Wonderful piece and rightly so an important process in research. Working with fieldwork professionals made me realize how important this is and also how it makes everything else smooth. In Marsabit, a rural setup in Northern Kenya, we had the area chief, village elders and enumerators sat round in a circle in what is called a ‘baraza’ locally to explain our purpose there, the engagement/period of days, our expectations, the importance and value of their work, and even compensation amounts. Many at times you need that ‘experience’ like with Jane to truly understand why something is done.

Thank you so much for sharing this reflection! You’re absolutely right—experiences like the baraza in Marsabit really show how essential community engagement and clarity are in making research run smoothly. Bringing together chiefs, elders, and enumerators not only grounds the work in local realities but also builds the trust that makes everything else possible.

Things like that remind us that research isn’t just about data collection, but about respect, dignity, and collaboration.